[This piece was first published exclusively to patrons at Final Fantasy VII: Camera and Composition – Part 2. What was originally an excerpt of the piece here has been edited to contain the whole text as of 5th January 2015. If you like what you see here and wish to support my writing while gaining access to patron-exclusive articles (one per month) and artwork, zoom on over to Patreon and sign up as a patron.]

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

In Part 1 we went over some of the basic ways Final Fantasy VII uses camerawork and scene composition to thread its themes by relying on almost invisible narrative techniques. We talked about how the ramshackle slums are represented compared to Shinra-designated areas to illustrate a gap between the classes of Midgar’s capitalism. In this, we saw how positive, navigable space differs from one to the other in how they ask the player to relate to these areas in the intersection of mechanics and visual composition.

And we touched upon a theory about the use of symmetry as a signifier of existential contentment. We rounded off the piece by suggesting Shinra is commonly represented as existentially harmonious, fitting into its role as an oppressive capitalist organization which currently organizes the whole world according to capitalism and oppressing its people. Its existence suits its essence. Likewise, a clear early location of Aeris’ existential centre is the Sector 5 church, Midgar’s sanctuary for the lifeforce of the planet and the one area that best encapsulates her narrative arc.

Now, we could spend a million words viciously dissecting every single camera angle to enjoy their juicy semantic innards, and all without leaving Midgar. But it’s time to move on just a little bit to look at a particularly exquisite narrative sequence that I’m sure is fondly remembered by all fans everywhere: the flashback to Nibelheim.

And where better to begin this analysis than… back in Midgar.

Okay, we’re actually on the very outskirts of Midgar. Cloud and company have just escaped the clutches of Shinra and rescued Aeris from her gruesome fate as a lab specimen, during which President Shinra met an untimely end at the hands of one ‘Sephiroth’. Along the way we picked up fan-favourite character Red XIII, so that’s good. We’ve ridden our crazy motorcycle and beaten the armoured tank boss, and now stand on the cusp of the great wide world beyond Midgar’s literal walls.

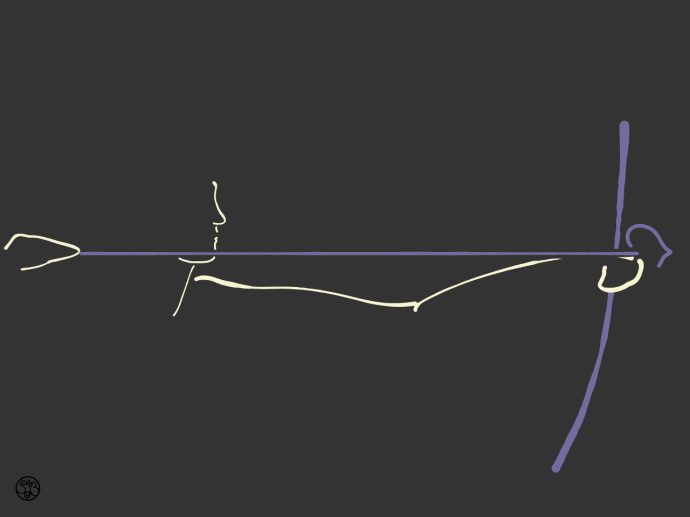

I quite enjoy this shot because it deviates slightly from what would become a tradition in Final Fantasy games: the beginning of an adventure into unknown territory. Typically you expect such a shot to occur on the brow of a cliff overlooking a beautiful expansive landscape, giving you a glimpse of the journey to come.

But here the party rests with their backs to the city of Midgar and we’re looking towards their faces (well, all except Cloud in this screenshot—he’s player controlled right now). While we can’t see the big open world they’re looking out towards from this angle, we can see them very clearly, which makes it an ideal angle for situating the characters as the focus of the scene and highlighting their past, here represented by an increasingly distant Midgar. Their future is unseen and unknown, whereas the past is accounted for as overcome (or at least escaped) ground. A bit of dramatic irony for returning players, here.

So in the fore- to mid-ground we have an abundance of positive space, for perhaps the first time in a non-Shinra-designated area, breaking off in the distance at Midgar’s looming, unassailable form. Even the colour palette suggests the future as brighter than that capitalist fortress.

As it happens, we actually do get a shot on the brow of a cliff (well, a highway) overlooking a beautiful expansive landscape just after the boss battle.

It’s actually a wonderful environmental shot in spite of a few odd characteristics: it doesn’t really show us what’s beyond Midgar specifically, since the horizon is obscured by the trio of Midgar scenery, far-off hills and an as-yet young sunrise. Instead we get a general idea of what’s next in the journey, which is to say, not-Midgar. And secondly, although this is the bit where Cloud and Aeris state their intentions for the adventure, they come across on-screen as insignificant.

To be honest I’ve a more lasting memory of the alternative ‘Leaving Midgar’ shot so maybe it’s a personal whim of mine to find more to recommend it.

Anyway, moving on, the player organizes their party and exits through the foreground. If you make a party full of boys, Tifa and Aeris will both comment on your unusual choice before they set off together. Hopefully they’ll find something in common to talk about.

The next area is the world map but it’s compositionally dull so let’s go straight to Kalm.

Kalm is a nice enough town. It adds a lovely shade of indigo to our encountered palette which is nice on the eyes. The architecture is rather distinctive but since this is a composition analysis I’ll leave it be. It’s somewhat of a well-to-do satellite town of Midgar, having profited off trade from the Mithril Mine further to the south-east as evidenced by through the shops’ inventories and various rare-ish items you can find about the place. And although the people here will never be the sort to join AVALANCHE they’re a hospitable enough bunch.

Anyway, this is the first place outside of Midgar we visit but we can see right away that it’s a townspace by the layout and the distancing and angling of the camera on the scene. The player can enjoy some downtime before meeting up with your party on the second floor of the inn to continue the story.

Aside from the reception area the inn only has one big room, which can’t be convenient if another party of adventurers were to show up. As luck would have it they never do. There are also only three beds but five party members. The game leaves their sleeping arrangement up to our imaginations.

This is the room where Cloud recounts what canonically will come to be known as the Nibelheim Incident, which he has decided is the best way to tell everyone about his relationship with Sephiroth.

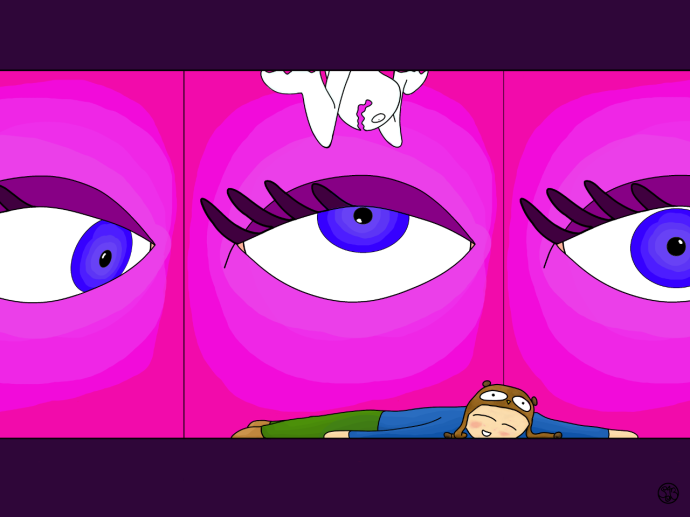

You’ll notice the room is bisected by an awkward tangle of pipes running along the ceiling. It’s a common feature for indoor areas in Kalm, although this room might be especially bad for how they intrude into the scene. The pipes separate the room into two rough portions: the right side, where everyone has gathered to hear Cloud’s story, and the left side, from where Cloud enters the scene. It’s possible that the pipes are a total accident but this could be an attempt to discretely division Cloud from the rest of the cast, perhaps in apprehension for their present expectations of him. What’s a bit of trauma between friends.

I mentioned this in the last post but I’ll repeat it here because it’s a nice bit of choreography: when Cloud begins talking to the group he’s situated centrally on-screen, but as he sets the scene for the flashback he turns around and paces away from the group, stopping here:

Now the pipes somewhat obstruct him on-screen, so the distance he has placed between himself and the party is mirrored in our own relationship with him through our diminished visual contact.

We have been given reason to suspect Cloud’s mental state at previous occasions where he has spoken confusedly with an unknown other, usually in times when unconscious or asleep, but this nugget of composition goes quite a way to specifically colour Cloud as an unreliable narrator in the tale to follow and foreshadow the twists in his arc much later.

The flashback opens in the back of a truck. Cloud, Sephiroth and a couple of Shinra MPs are on a mission to Nibelheim to investigate a series of monster attacks originating from the malfunctioning Mako reactor nearby.

When the scene opens Cloud is right up in our face in the foreground, giving a strong impression of his presence in the scene. One of the first things he does, after talking about the weather, is to turn to the guard on the left to inquire into his health. The nuance here is it turns out later that, in the events as they actually unfolded, the motion sick guard is actually Cloud and the person in Cloud’s shoes is actually someone named Zack. For simplicity’s sake I’m going to call the spiky-haired fellow in the screenshots ‘Cloud-as-Zack’ and the Shinra MP ‘Actual Cloud’ when I need to distinguish between the two.

From the way this scene is shot and choreographed, Cloud-as-Zach carries himself as a midpoint between Actual Cloud and Sephiroth, Cloud’s mentor-cum-nemesis. We generally learn through this flashback that Sephiroth had a huge impact on Cloud growing up, informing his career direction as well as the way Cloud chooses to model his behaviour, lasting even to the present. The Nibelheim Incident will show an overall trend towards distancing between Cloud and Sephiroth, which we would expect given what is to transpire. It’s telling, however, that in recollecting the events Cloud exaggerates his closeness to the villain.

Almost as if the ghost of Sephiroth still has some hold over him, hint hint.

Anyway, Cloud says he’s never had motion sickness but eagle-eyed players might notice he gets an upset tummy if you play the Speed Square at the Gold Saucer too many times. At various stages Cloud will also sympathise with Yuffie and give her advice on how to handle her motion sickness. What’s interesting to note is how Cloud has removed his susceptibility to motion sickness from his life by believing wholeheartedly the lies he tells himself about his identity. In essence, this scene—and therefore the entire flashback—commences by centring Cloud-as-Zack as the focus of identity, which is facilitated by immediately acknowledging and passing off the discrepancy of Actual Cloud’s motion sickness on a prominent yet ancillary third party. With the contradiction paved over, Cloud’s mind sails on.

Once the introduction and briefing is done, the truck comes to an abrupt stop. The driver spins in his seat to report they’ve rammed into something.

People don’t normally spin on the spot or stand on the car seat so there’s an unavoidable bit of slapstick humour when he flicks right around like that. Oh Final Fantasy!

Notice the driver’s hesitation in acknowledging his supervisors in the plural. Cloud acts the bigshot veteran when he’s a mercenary in Midgar but this scene reveals how much of a rookie he really was.

Now then. We have ‘something strange’ to deal with.

IT’S A DRAGON.

The camera descends from an aerial viewpoint and twirls behind our two party members to frame them against the huge beast. It’s such a splendid shot because it conveys the severity of the foe you’re about to face while both uniting Sephiroth and Cloud as teammates and dividing them in terms of strength. The right side of the screen is weakness and death; the left side is power and life.

The fight lasts less than a minute but it’s packed full with exquisite ludological storytelling so I’ll give a quick summary. It’s all related to composition anyway because I say it is and what I say goes.

- The dragon attacks Cloud with low-level magic, but it’s so strong anyway it kills him five times over.

- Sephiroth uses high-level magic to completely revive Cloud. You’ve never even seen the materia he’s mastered.

- The dragon uses the same low-level magic on Sephiroth. It does zilch.

- Sephiroth attacks the dragon normally, dealing damage far beyond anything you’ve yet encountered.

- Cloud has the opportunity to attack. He deals a pathetic amount of damage.

- The dragon attacks again, either burning Cloud to a cinder or warming Sephiroth gently.

- Sephiroth immediately returns the attack and slays it.

I like how Sephiroth goes out of his way to revive Cloud to full health when he really doesn’t need to. It reinforces the idea that, even though Cloud was far outmatched by his mentor, they were still kind of a team and they co-operated within their abilities. It’s also a nice way to humanize Sephiroth a little, since we only have a short space of time when he’s not characterised as the mad monstrous destructive villain. He used to give life.

Once the battle ends, we cut to a Kalm-based Cloud reiterating how wonderful Sephiroth-senpai was. We’re going to see a few of these interruptions to remind the player this is Cloud’s telling of events and everything we see might not be everything that happened. Sometimes the interruptions extend inward into the flashback scenes themselves, with the onscreen character of Cloud physically or verbally[1] reacting to something said by Barrett or Tifa in Kalm. We can gather from this that the reality of Cloud’s story is especially fluid.

You remember what the inn looks like so we’ll scoot along to Nibelheim.

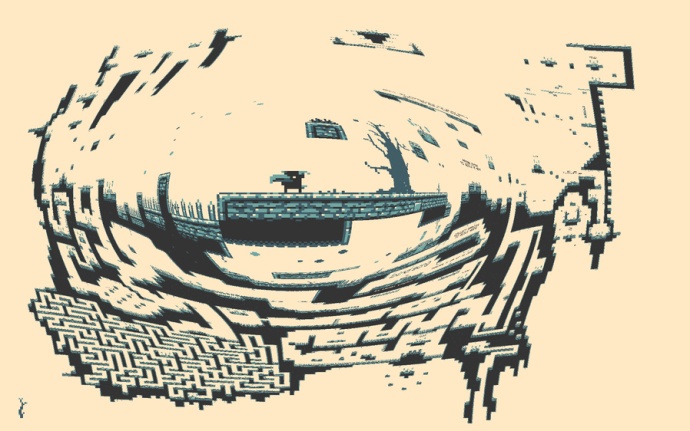

It’s a grand introductory shot for the town. You can see where the dust and mud becomes paving which gives a sense of the borders between Nibelheim and not-Nibelheim. There’s a crappy looking truck over there, a few barrels and that. White picket fences to suggest homeliness despite the grub.

Although it’s expected to be a Cloud-designated area, Sephiroth is first on scene. He walks into a central position in the mid-ground and turns to look just off the camera. From here he’s framed between the burgeoning pavement and the town’s entrance posts as if standing on the edge of one’s porch. He asks Cloud what it feels like to come home, with the subtext being Sephiroth has never had anywhere to call home and seeks to understand this seemingly basic facet of humanity. What he doesn’t know is he stands in the doorway of his own hometown.

Normally in Final Fantasy VII, a character in dialogue facing towards the camera is staged for dramatic effect, the camera lens representing somewhere inside of themselves to which they speak, similar to a soliloquy in theatre albeit with their musings heard and acknowledged by other characters. So when a character turns to the camera to say something, Something’s Going On.

In this case, Sephiroth is speaking to an off-camera Cloud-as-Zack about his past, foreshadowing the villain’s upcoming identity crisis. It serves to deliver important exposition—this much is clear.

A funny thing happens next. Sephiroth declares it time to continue and advances into the background, now facing away from the camera. His body language has shifted from open to stand-offish.

Cloud and company enter into the space behind Sephiroth. Now each character frames Cloud as if to box him in. When a player goes to speak to each character the sensible thing is to take the nearest route, so the player’s accustomed movement naturally limits Cloud to this human enclosure, our behaviour precluding a lot of the positive space in the foreground’s flanks. Although I doubt it came across strongly in anyone’s actual experience of the scene, looking at it now Cloud’s homecoming has a bit of an initially claustrophobic vibe.

Curiously, Cloud-as-Zach doesn’t enter from the right-hand side of the foreground, which is where Sephiroth was directing his enquiries, but from just left of centre. Maybe it means nothing, just a goof. Maybe Sephiroth was addressing the Shinra MP on the right, who might be Actual Cloud.

Maybe the conversation never really existed and what we witnessed was a bit of theatrics on Cloud’s part. We never really know how much of Sephiroth as represented here is accurate to his ‘real’ character and how much is Cloud’s embellishment, and the oddity of Cloud speaking from off-camera could signal him speaking in the first-person, from the inn in Kalm.

To me, because of how Sephiroth is represented on-screen and how Cloud isn’t, and given how it segues from Cloud’s awe at his mentor, the first half of this scene feels like a conversation between the two characters presently unfolding inside the head of our storyteller. As the plot unfolds we learn there actually is a little bit of Sephiroth lurking in Cloud’s consciousness courtesy of Jenova cells, so this is a possibility.

If we adopt this interpretation, that it’s a conversation between Cloud and Sephiroth taking place in our hero’s mind, it shifts the nature of the camera from the second-person of the game as acting narrator to the first-person of Cloud as storyteller. Well, we know the Nibelheim Incident as related here is really just the imaginings of Cloud and that this narrative here told obeys his confused, disjointed recollection, so it’s not a big leap to nudge the camera along this reference. What it means, though, is that as a player we are repeatedly transitioning between first- and second-person perspectives throughout the entire sequence without displacing our sense of identity. Or put another way, the flux of perspective further marries us to Cloud as a character in our identity and worldview.

The beauty of all this is, however this exchange actually went down it remains consistent within the perspective of the game on a whole. Cloud is convinced the events as he tells them were the events that occurred. The distinction between what’s ‘real’, what’s only ‘real to Cloud’ and what’s full blown ‘delusion’ is, right now, immaterial to the player. From our perspective of identifying as Cloud, it all happened as Cloud says it happened: we experience these scenes as Cloud believes it to have gone down. We may suspect Cloud to be an unreliable narrator and to be a bit off in the head, and we may cop to Tifa’s repeated, pointed silence as indicating something amiss with Cloud’s story, but still we are bound to the perspective granted us.

There is a whole big thing here about identity and perspective that we could go even further into but it’s another day’s work.[2] We’ll shelve the topic for now and continue with Nibelheim.

I don’t know if that’s a translation error or if Cloud is supposed to slip into the present tense. It’s not exactly composition though so…

Nibelheim is recognizably A Town. It is shot like most other towns we’ve come across; it’s at a jaunty angle and the buildings and positive space are all knees and elbows so it resembles the poorer slums of Midgar rather than the clean horizontal and vertical lines of Shinra.

Sephiroth says we may visit our family so let’s do that.

Cloud tries to avoid the topic but Barrett and Aeris are having none of it, so we do get a glimpse into his family life. He describes his mother as “a vibrant woman” but notes…

Which is an odd way of saying she burned to death in a horrible fire that engulfed everything he had ever loved.

As you’ve guessed, Cloud is not very good at dealing with his mother, lovely as she is. The camera here is tonally consistent with that vibe—distant and removed rather than emotionally involved in the landmark homecoming event. Compare that to the first time we enter Aeris’ home and the scene with her mother.

The camera is closer and the angle is softer. Here the family are placed centrally in the shot, rather than focusing on the distance between them as in Nibelheim.

As it happens, when Cloud stayed the night at Aeris’ house he had a little flashback to Ma Strife clucking over his relationship status. The scene repeats in the Nibelheim Incident sequence but the context is drastically different: whereas before they were private recollections of the comforts of home, now they’re being publicized for a hungry audience while couched within the trauma of the events to follow. So the telling of Cloud’s and his mam’s conversations are here broken into fragments transitioned by a flash of white and the roar of static or wind, upsetting any warmth the event might convey and distorting the memory. A certain amount of that is to disrupt Cloud’s realization of true events—hiding his reveal that he isn’t really in SOLDIER when she comments on his uniform, for example—which is a transition effect repeated elsewhere when irregularities in Cloud’s story risk acknowledgment.

Transition effects are good at establishing a story’s demeanour so it’s good to note them once in a while.

So Cloud regales us with fragments of his short stay at home, and there’s a nice few touches of horror embedded in the choreography. While Cloud remains stationary in each clip, his mother hovers around him and moves about the house between shots. The effect of her movement is first to deposition her in relation to Cloud with each transition—there is something frightening about opening into a scene and seeing a figure imminently approaching you. As the transitions come quicker and quicker, Cloud’s position in the house remains fixed to one point while his mam’s becomes more erratic and animated, coinciding with her ‘barrage’ of questions into her son’s life.[3] Her constant displacement gives the impression that Cloud is being surrounded and cornered, rising our anxiety so that we share Cloud’s apprehension for the scene. When he breaks it off, it’s a relief.

You can also visit Tifa’s house. There are three short things to note here—Tifa’s presence, Tifa’s letters and Tifa’s piano.

First is Tifa’s speech bubble, which gates our entry to her house, then her room, then to ‘interact’ with some of her things. Tifa is never visually represented in this room so it’s a good way of denoting the space as fundamentally, privately hers. Cloud and the player must explicitly admit to her to invading her privacy for us to be able to look around the place, forcing us to recognise the interpersonal impact of our wandering curiosity and consider ourself through her eyes for a change. Even the affirmative answer to “Did you read it? My letter?” admits this as a violation. If you’re the sort to respect people’s spaces, you’re likely to lose a bit of yourself in the compulsive quest for secrets.

Unfortunately, Cloud kind of laughs at the severity of his transgression by making out she had orthopaedic underwear. Dick move, Cloud.

Second is the letter on Tifa’s desk. There’s three letters in Tifa’s room throughout the course of the game—you can pick up the others when the party passes through Nibelheim later on. The first letter you can read now, though, and it’s one of Tifa’s childhood friends describing how he’s adjusting to life in Midgar and murmuring about his feelings for her. The second letter details Shinra’s appropriation of Nibelheim following the Incident with Sephiroth and speaks of how all the ‘townsfolk’ now are actors employed by Shinra as a cover story. I read elsewhere that Nibelheim used to have its own special dialect that was essentially lost due to Shinra’s overtaking of the town. Such is the soul of colonization.

Final Fantasy VII doesn’t have an internal database or collectible textlogs to allow us to scry into the world beyond Cloud’s adventure. The closest we come is this second letter which is marked as a normal point of interest without becoming trite and cliché from overuse. Collectible-structured curios carry with them a formalized narrative of indulgence and accumulation so that their value as objects is distributed as value as playthings. Personally I find this often corrupts their worth as vessels for knowledge and meaning[4]; I’d much rather see Tifa’s letters become the model for distributing worldbuilding than what is currently the case in audio- and textlogs.

The third letter is from Tifa’s mentor, Zangan, and speaks of how he found and rescued her immediately after the events told in this flashback. To get this letter you need to access Thing Three: the piano.

If Cloud plays the piano in Tifa’s room in the flashback, he’ll recite a tune. Later on in the present, the player has to play the tune on Tifa’s piano in order to get Tifa’s best limit break and the last letter. I’m looking at this now and it’s funny that back then we all accepted as normal how contrived this is—“oh yeah just memorize the random-ass tune Cloud plays for no reason so you can recite it ten hours later in order to get an item you would have had no way to anticipate.” Were we really such expert sleuths? Were we super patient? Or did we just natively depend on strategy guides as the done thing? It’s almost endearing how expressly Tifa’s piano is a relic of the past.

Anyway, eventually you return to the inn.

More foreshadowing from Sephiroth-senpai.

The next day the group assembles to head up the mountain towards the reactor. Time to meet your guide: much to Cloud’s surprise, it’s Tifa! However, she plays it cool on being reunited with her childhood friend. Actually she doesn’t even remark on Cloud at all. Strange.

They’re ready to embark but a local wants to take a quick picture of the legendary SOLDIER, Sephiroth.

That’s every one of them saying “Cheeeeese!” including the soon-to-be murderous villain. Haha, good times.

This photo will show up later in the game as proof that Cloud-as-Zach is not actually Cloud, which is a fantastic bit of supra-diagetic textual metaplay. I love it when a media text uses in-text media to reference and fold back the fictional reality. When successful, it can add weight to the world and its sense of contiguity through in-world use of tools and items in appropriate ways to their real-life functions. Even though it’s counter-intuitive that an in-game photograph which reveals the player’s camera to be a sheer and utter lie should further substantiate the gameworld rather than crumble it, here it works, and to wonderful effect.

But that’s an area of media studies that’s best left to its own specialized analysis. This might be a good point to take a break and wrap up part 2 of this series. Part 3 will take us up Mount Nibel and into the birthplace of Sephiroth’s villainy, whereupon we’ll discuss the connecting themes of nature and technology, foreshadowing through Norse mythology, and, of course, Sephiroth’s existential folly.

Bonus Senpai Picture

[1] That being said, the rules that inform us whose speech bubble belongs to whom doesn’t really establish a line to separate Cloud’s Kalm-based speech bubbles from Cloud’s flashback-based speech bubbles. For all we know, every piece of dialogue in the flashback is extra-diagetic to the setting of Nibelheim and is actually Cloud sitting at the inn in Kalm pulling funny voices to impersonate the speaker.

[2] I wrote on the subject in ‘Framing Identity – or: How Can I Be Both Lee and Clementine?’

[3] Questions that are by no means out of the ordinary for a mother to be asking or scary to find asked of oneself.

[4] More on this in ‘Exploring A Dark Room’.